HMS Neptune, lead cruiser of the Royal Navy's Force K, stationed at Malta in 1941

In the early morning hours of Saturday, December 19, 1941, one of the worst disasters in the proud history of Britain's Royal Navy unfolded off the coast of North Africa when HMS Neptune fell victim to an enemy minefield. For many years thereafter, the fate of the battleship and its crew remained shrouded in mystery.

Other disasters like the loss of the battlecruiser Hood on May 24, 1941, with the death of over 1400 sailors, caused a crisis of morale amongst the British people. The sinking of the formidable HMS Prince of Wales by Japanese torpedo planes in the South China Sea on December 10 of the same year had a similar impact. These setbacks received widespread attention at the time, and the British Admiralty promptly informed next of kin what had happened to their loved ones.

After the sinking of HMS Neptune, the casualty Reporting Office of the Royal Navy in Devonport, England, sent the usual cryptic messages to next of kin over the Christmas holiday of 1941. Then, the British Admiralty slapped a top-secret order on the circumstances surrounding the incident off the coast of Libya. The subsequent inquiry report remained unseen and unopened in military archives for 33 years. Next-of-kin could not discover what had happened to their loved ones. Many held on to the vain hope that somewhere, somehow, their sons or husbands were still alive.

Alan and Fanny Winsor living in Triton West, Newfoundland, received the grim news by telegram on Boxing Day, 1941. We regret to inform you that your son, Bertram P. Winsor, is missing while on active war service. Bertie's younger brother, Chesley, home on leave, delivered the devastating news to his mother and father.

The two brothers, Bertie and Chesley, enlisted together in 1940, part of the tenth contingent of young men who answered Governor Sir Humphrey Walwyn's call for volunteers to join the Royal Navy. The two brothers trained at Portsmouth on the southwest coast of England.

The two brothers, Bertie and Chesley, enlisted together in 1940, part of the tenth contingent of young men who answered Governor Sir Humphrey Walwyn's call for volunteers to join the Royal Navy. The two brothers trained at Portsmouth on the southwest coast of England.

After their training, Chesley joined the G class destroyer, Greyhound, operating in the eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, Bertie received his posting to the much larger and more powerful cruiser, HMS Neptune, the lead warship in Force K, a raiding squadron operating out of Malta.

The squadron was tasked with destroying enemy ships and their escorts ferrying supplies to German forces in North Africa. Winston Churchill himself stressed the importance of their mission in a message to the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Station, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham: If any supplies get through, you have failed in your duty.

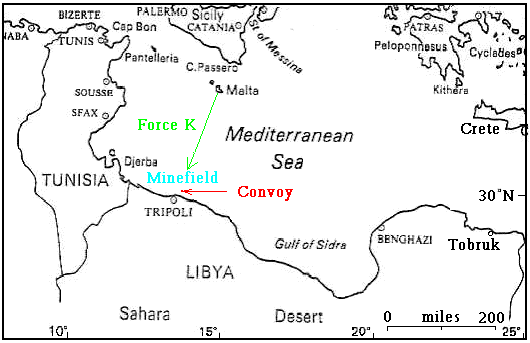

When Force K departed Malta on the evening of Friday, December 18, 1941, it included three cruisers, Neptune, Aurora, and Penelope, along with four escort destroyers, Kandahar, Lance, Lively, and Havock. Ajax, the flagship of Rear Admiral Rawlings, a fourth cruiser, could not sail because of mechanical problems.

Special intelligence signals intercepted by the British on December 18 indicated that a large convoy of German and Italian ships had left Italy bound for Tripoli and Benghazi with reinforcements, heavy tanks, artillery, and other supplies for General Rommel's Afrika Korps. Further Italian messages indicated an abundance of enemy naval activity along the Libyan coast. Destruction of these targets could alter the course of the fighting in North Africa.

On short notice and without adequate briefing, Vice-Admiral at Malta, Sir Wilbraham Ford, ordered Force K to sea at 6 pm, December 18, directly towards Tripoli. Vice-Admiral Ford deemed the situation so critical that Rear-Admiral Rawlings, who should have sailed with Force K as the overall commander, was left behind on the golf course. Ford replaced him with Captain Rory O'Conor.

Rawlings never dreamed that his ships would sail without him and was outraged on his return to base. His absence would prove disastrous.

After clearing Malta Harbor, Captain O'Conor increased speed to 30 knots. A storm was brewing, and by early evening, it was pitch black.

At 1 am, Saturday, December 19, Captain O'Conor gave the order to reduce speed. Force K had now closed to within 20 miles of Tripoli and was just five miles from known minefields laid by the French and the Italians at the beginning of the war. At this position, there should have been no danger to his warships, but a few minutes later, the darkness lit up with the flash of an explosion off Neptune's bow. Aurora and Penelope had immediately altered course to starboard when they, too, were buffeted by large blasts.

Force K had blundered into an uncharted minefield. The crippled Aurora and the slightly damaged Penelope manoeuvered out of the danger zone. Neptune was less fortunate. Two more powerful explosions rocked Captain O'Conor's ship as he tried to pull away to safety. The cruiser now lay helpless in enemy waters without steering and power. Dawn approached with the ever-present danger of an air attack.

The lead destroyer, Kandahar, tried to reach Neptune to attempt a tow, or at the very least, to save the crew. It was not to be. The aft end of the destroyer was torn away by an explosion, and it lay dead in the water. None of the other ships attempted to lend assistance. To do so would have been suicide.

At 4 am, as the two ships drifted on the strong current, Neptune took another powerful explosion amidships, smashing its hull. It drifted for another 36 minutes before it turned over and sank. At dawn, those left on the Kandahar looked out over the disaster zone where Neptune had disappeared. The ship and its crew of 766 had vanished without a trace. No debris field, no oil slick, no floating bodies, and of greatest concern, no survivors were visible.

For all of Saturday, December 19, Kandahar drifted ESE for 50 miles. When darkness came, the destroyer, Jaguar, operating in heavy seas, located the stricken warship and attempted the tricky rescue of the crew. One hundred seventy-eight were taken off. Another 73 were casualties. Jaguar fired a torpedo into the abandoned destroyer and sent it to the bottom.

Other than official telegrams to the next of kin, there was no public acknowledgment of the disaster. A court of inquiry convened in Malta on December 24, 1941. The board's report arrived at the Admiralty in London two months later, on March 3, 1942.

And there the report sat, in top-secret limbo until 1974. Not even Prime Minister Churchill knew of its existence.

For those who reviewed the report 33 years later, the conclusions revealed many disastrous errors coupled with petty squabbles between senior officers. Captain O'Conor had indeed steered his ship into a minefield laid by the enemy six months previously in May and June 1941. That much was clear. Surprisingly, the submarine service knew of the minefield's location, as did some officers of Force K. They had not passed this information on to the captain of Neptune. Rear-Admiral Rawlings also knew the precise location of this new minefield, and had he sailed with Force K, the disaster would have been avoided.

The hurried dispatch of Force K from Malta, without Admiral Rawlings, appeared to have been a deliberate act by Admiral Ford. Tensions and bad feelings between the two were well known on the base.

Bertie Winsor, back row, far left, and his shipmates on Neptune. The picture had been stored in the attic of a New Zealand home for 75 years. Bertie's sister, Bride, identified her brother. She was eight years old at the time of the tragedy.

Six named Neptune casualties are buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Tripoli. Twenty other graves are marked Known unto God.

Able-seaman, Norman Walton, was the lone survivor of the Neptune disaster. On Christmas Eve, he was picked up by the Italian torpedo boat, Calliope, after drifting some 75 miles on a Carley raft for five days. Walton's shipmate, Albert Price, was also alive and clinging to the raft. In the rough seas, while Calliope manoeuvered alongside, the raft caught a large wave and went under the stern. The propellor killed Albert Price.

Norman Walton remained a prisoner of war until 1943. He died in 2005.

Bertie's brother, Chesley, survived the war. He narrowly escaped death seven months before the Neptune disaster when Greyhound was attacked and sunk by German dive bombers in the eastern Mediterranean on May 22, 1941. Chesley jumped into the water and swam towards a raft filled with men when the call came to abandon ship. With another enemy dive bomber approaching and firing on the raft, he dove underwater. When he surfaced, everyone in the raft had been killed. Several days later, he was rescued by another destroyer, HMS Kandahar.

Bertie's memorial in Triton, Newfoundland, indicates that the action took place on December 25, 1941. Given the secrecy surrounding the sinking of the cruiser, this incorrect date appeared on many memorials in the UK, South Africa, and New Zealand, where most of the seamen originated.

NB: The Neptune wreck was discovered off the Libyan coast in 2016 by HMS Enterprise, a hydrographic ship of the Royal Navy. She lies in deep water--over 150 meters. Her exact location remains a secret to deter wreck hunters.

It took ten years for all the pieces of Bertie's story to fall into place. Special thanks for some details go to Bertie's sister, Bride, in Triton; his nephew, Chesley Jr., and Commander John Mcgregor, Royal Navy, retired, and chair of the Neptune Association. Shortly after we began our correspondence, Commander McGregor sent me a copy of the New Zealand photo.

Location maps courtesy of the Neptune Association