Lieut Cyril Gardner

Two Cousins at Monchy-le-Preux

Caribou Monument Pointing Towards the Battlefield at Monchy-le-Preux

During the Great War, L/Cpl. Beadon Colbourne and 2nd. Lieut Cyril Gardner were brothers-in-arms and cousins by kinship. Colbourne from Bishops Falls, Newfoundland, and Gardner from British Harbour in Trinity Bay, traced their common ancestry to John and Elizabeth Colbourne who settled at Twillingate in 1782.

Gardner joined the First Newfoundland Regiment on February 5, 1915, at age 29. Colbourne joined 5 months later, on July 1 at age 28.

Because of the different enlistment dates, their active service with the regiment did not overlap until late fall, 1916.

On August 20, 1915, Pte. Gardner had completed training at Ayr in Scotland and was posted with his regiment to Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula where the British were engaged in a bitter struggle to defeat Turkish forces and advance on Constantinople.

The disastrous Gallipoli campaign ended in December 1915 with the withdrawal of allied forces. A month before the withdrawal Pte. Gardner was promoted to lance-corporal.

After Gallipoli, the First Newfoundland Regiment returned to Europe via Marseilles, France, and joined other allied forces in the trenches of the Somme. Colbourne was still attached to the training base at Ayr. He embarked for advanced battlefield training at Rouen in France on June 26, 1916, shortly before the disaster at Beaumont Hamel.

Among the 800 who charged the heavily defended German lines at Beaumont Hamel on July 1, 1916, was L/Cpl. Cyril Gardner. He received a gunshot wound to the thigh but recovered quickly and returned to his regiment in August. His younger brother, L/Cpl. Edward Gardner was killed.

For the next eight months, L/Cpl. Gardner and Pte. Colbourne served together through some of the toughest fighting of the war.

On October 12, 1916, the rebuilt First Newfoundland Regiment which had nearly been annihilated at Beaumont Hamel attacked German trenches at Gueudecourt. The poorly planned assault resulted in 250 Newfoundland casualties with hardly any ground gained.

At Gueudecourt, newly promoted Sergeant Gardner won the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) when with two other men he charged a large German bombing squad, defeated them, and took one officer and fifteen men prisoner (London Gazette, December 1916).

A few weeks after Gueudecourt, Sergeant Gardner became Company Sergeant Major while Pte. Colbourne received a promotion to lance corporal.

The next major engagement came in late January at Les Boeufs where the First Newfoundland was placed in a support role to the Border Regiment of the British Army. Gardner was leading a contingent of stretcher-bearers into no man's land to recover casualties when he noticed a German officer and a large group of armed enemy soldiers in a trench that had been missed by the Borderers. With quick thinking, he demanded and received the surrender of 72 Germans. (London Gazette, March 1917).

For his gallant action, Sergeant Major Gardner received a bar to his DSM. In March, he was again promoted, to 2nd. Lieutenant.

After a period of illness in January and February, L/Cpl. Colbourne returned to the regiment in mid-March as preparations began for another 'great push' by the allied forces. The offensive which became known as the Battle of Arras began on April 9, 1917, with the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians.

The First Newfoundland's role in the Battle of Arras began with the Regiment moving into position in front of Monchy-le-Preux on Friday, April 13. in a sign of the inept planning surrounding the operation, the men were ordered to advance at 2 pm. It was only when the commanding officer pointed out the impossibility of his soldiers moving forward in broad daylight under German observation that the order was canceled.

On a cold Saturday morning, April 14, 1917, at 5.30 am, 597 men and twenty officers jumped off and began their advance on Infantry Hill and the German positions. The First Essex Regiment, jumping off at the same time, covered their left flank. There was no protection on the right flank--a fatal flaw in the planning. The line of advance was akin to blowing a long balloon into enemy lines.

Once the Essex and the First Newfoundland neared the top of Infantry Hill, the enemy opened a deadly artillery barrage all along the line of advance. Withering machine-gun fire opened up on their flanks and from the front.

L/Cpl. Colbourne died as he moved forward with Lieut. Leo Murphy.

A Pte. Squires, who became a prisoner of war during the battle, later testified to being in a trench with 2nd Lieut. Gardner when they were hit by shellfire. Gardner was one of several killed by shrapnel.

The official war diary of the First Newfoundland Regiment indicated that the battalion began the day with 597 men and 20 officers. Of these, 470 other ranks and 17 officers were listed as missing, wounded or killed.

*********************************************************************************

Remembering Levi Normore

The grave markers in the well-kept cemetery are a testimony to the long and sometimes tragic history of the villages on Long Island, Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. With the island's declining population over the years, this final resting place has become a secluded spot. Located as it is, close to the wild north Atlantic, a visitor soon becomes aware of the mournful soundings of the ocean swells pounding on the headlands a kilometer away--a continuous funeral chant for the dead.

I was drawn to this cemetery on a foggy August morning in 2011, first, by its remarkable solitude, but also by the obvious efforts of the living to preserve the memories of children gone too soon, of mothers and fathers taken away, of grandparents long departed, and of sons lost to war.

An unusual marker, a modest obelisk no more than two meters high, stands prominently near the middle of the cemetery. On the east face of this monument a simple inscription: In Loving Memory Of Number 2425, Levi Normore, Killed In Action At Monchy-le-Preux, France, April 14, 1917. He Gave His Life For His Friends.

At the time, I knew little about Monchy-le-Preux or about what had happened there in 1917. I had seen Levi's name as one of many on the Island's war memorial--the fatalities of WW1. But Levi's story soon developed into a fascinating journey through the backwaters of the early twentieth century and the unimaginable violence of the Great War.

In the spring of 2013, the journey took me to Beaumont Hamel in northern France where Levi's name is inscribed on the memorial to the gallant young men of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment who died on the battlefields of Europe. It also led me to Monchy-le-Preux, a sleepy village, twelve kilometers southeast of the city of Arras, where an unspeakable tragedy unfolded in the early morning hours of Saturday, April 14, 1917.

Just outside the village, I walked up the gently sloping fields that had once been the line of advance for the men of the First Newfoundland Regiment and those of its sister regiment in the 88th Brigade, the First Essex. A hundred years later, the same patches of woodlands, the Bois du Vert, Machine-gun wood, the Bois des Aubepines, still rise ominously through the early morning mist. At dawn on April 14, 1917, these woods teemed with the battle-hardened soldiers of the Third Bavarian Division of the Imperial German Army.

Fields over which the Newfoundland Regiment advanced in 1917, Bois du Vert at the top

Fields over which the Newfoundland Regiment advanced in 1917, Bois du Vert at the top

***

When Levi Normore joined the regiment on April 4, 1916, he was 26 years old, a full six years beyond the average age of enlistment. He was leaving behind on Long Island a young woman he planned to marry. A family and a peaceful life tied to the rhythm of the seasons lay in the future. Levi and his wife-to-be had already built a cozy home with twin stone fireplaces and a cement foundation in a sheltered cove at the entrance to his home village of Cutwell Arm.

***

From the trenches just east of the village, Levi and 590 fellow soldiers of the First Newfoundland jumped off at 5.30 am on that Saturday morning just over a century ago. A short and ineffective barrage by British artillery preceded their advance. Small numbers of German soldiers could be seen abandoning their front-line trenches several hundred yards away and retreating.

To the left of the Newfoundlanders, 923 men of the First Essex jumped off at the same time. The objective was Artillery Hill, the crest of the slope rising from the flat farmland immediately in front of Monchy-le-Preux.

By 6.30 a.m., both regiments seemed to have reached their objectives but then the situation changed dramatically. Well-hidden German defenders opened up with machine-guns from the wooded areas on the flanks of the advancing soldiers. German artillery set down a devastating barrage on the open field. The main body of Newfoundland soldiers disappeared over the crest of Infantry Hill and was annihilated. The Essex, caught in the German crossfire, fared no better.

By the end of the morning, the Essex had suffered losses of 661 men, killed, wounded, or missing. Several hundred of those were later confirmed as prisoners of war.

The First Newfoundland suffered losses of 487 men, 80 percent of the soldiers that had begun the advance in the early morning. The tragedy of Beaumont Hamel had repeated itself 10 months later. Among the dead was Levi Normore.

One thousand one hundred forty-eight men had been sacrificed for no purpose.

***

Senior officers of the British forces lost no time in painting a rose-tinted picture of the disaster. The soldiers had gallantly thwarted a major German offensive, said some. It would have taken 50,000 soldiers to recover the village, had it fallen, said others. The tragic narrative was transformed to focus on a small band of Newfoundlanders who fought off a much larger group of Germans threatening the village later in the day.

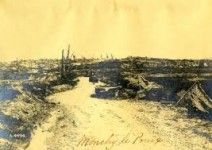

All that was left of Monchy-le-Preux

Twenty years on, military historians sought to uncover the truth about the debacle at Monchy-le-Preux. They concluded that the plan of attack, drawn up by an 88th Brigade major, was deeply flawed.

Later research, using German military records, indicated that the Third Bavarian Division was experimenting with a new tactic in defensive warfare, the elastic defense. Simply put, it consisted of luring your enemy into a trap.

German records also indicate that Monchy-le-Preux was not an objective for the Third Bavarian Regiment on April 14, 1917. A year later in the spring of 1918, German forces captured the village in their last spring offensive of the war. A few months later, it was recaptured by Canadian troops in the final phase of the conflict.

***

Today, a bronze caribou looks out over the battlefield where Levi and his comrades died. The fields over which the soldiers advanced have long since been returned to farmland. Occasionally, a hiker picks up a brass button from the uniform of a fallen Newfoundland soldier.

Commonwealth War Cemetery at Monchy

After 100 years, Levi's home on Long Island has largely melted into the undergrowth but if you pull aside the tangle of wild raspberry and willow, you will find that the concrete foundation has stood the test of time.

Clyde Croucher (foreground), a well-known local historian, took us to the site of Levi's home in Beaumont

*************************************************************************