Back in 1899, when everybody sang auld lang syne...

Steve Goodman, The Twentieth Century is Almost Over.

Expressions of sorrow and condolence appeared regularly in newspapers of the day. A notice in The Twillingate Sun in October 1891 was typical: We learn that diphtheria has been prevalent of late and that a good many cases have proved fatal. We are sorry that Mr. Samuel Short [of Ward's Harbour] has lost three children from the disease.

Settlers in outlying communities along the northeast coast of Newfoundland in the latter part of the twentieth century faced overwhelming health challenges. Life expectancy hovered around 42 years for men and 47 for women.

Just as today, La grippe (influenza) was common and often deadly for the elderly and young children, so too for Quincy, winter fever, the Spotted Demon, and Phthisis.

To our ancestors, these very words brought fear and foreboding. Perhaps no news was more terrifying than learning that the Strangling Angel--Diphtheria, was on the loose. The dread disease received its name from the development of a greyish membrane in the shape of angel wings on the tonsils, which quickly expanded to completely obstruct the windpipe and suffocate the victim.

When Great-grandmother, Martha Earle, lay dying in Island Cove, Notre Dame Bay, on Wednesday, April 6, 1892, five days after giving birth, she was leaving behind a family of four healthy boys ranging in age from eight to thirteen. To protect them from the disease, Great-grandfather had moved the children to another household in Lush's Bight, a mile away.

Martha was pregnant when she developed Diphtheria. The infant, John, born on April 1, was already doomed and certainly without his mother's care, he could not survive. On Good Friday, April 15, 1892, the Strangling Angel claimed him, as well.

The highly contagious disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae claimed 40 to 50 percent of children in the area over a ten-year period from 1885 to 1895. In many of the households, multiple children fell victim to the disease.

In the fall of 1890, Lily, four years of age, Herbert, two, and John, just three months, the children of John and Selena Parsons of Lush's Bight, died within a week of each other. To lose one child was a tragedy, to lose all three was a calamity.

There was little comfort even in their church. Most clergymen and lay-preachers viewed such diseases as either a test of faith or a punishment from God for sinful practices, a belief cemented in biblical orthodoxy as in 1 Corinthians 11:30, that's why so many of you are weak and sick and a considerable number are dying.

Or, the work of Satan, as in Job II, vii.

Unable to find solace and understanding in the confusions of the spiritual realm, people sought guidance from other sources. Newspapers carried sensational details of miracle cures for various ailments often accompanied by fabricated testimonials from doctors and from the formerly afflicted.

A report in the Twillingate Sun for January 25, 1890, proclaimed one such cure. The following remedy was discovered in Germany and is said to be the best known: after the first indication of Diphtheria in the throat of the child, make the room close, then take a tin cup and pour into it a quantity of tar and turpentine, equal parts. Then hold the cup over a fire so as to fill the room with fumes, the person affected will cough up and spit out all the membraneous matter and the Diphtheria will pass off. The fumes of the tar and turpentine loosen the matter in the throat and this affords the relief that has eluded the skill of physicians.

Ineffective as the remedy was, it became common practice in many communities. There were few, if any, alternatives. Medical science at the time was in its infancy in terms of understanding the nature of common diseases.

Antitoxins and vaccinations were many years down the road.

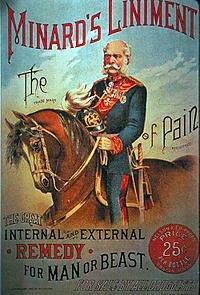

Minard's Liniment and other patent medicines filled the void--all claiming to be cure-alls for a host of afflictions, Rheumatism, Neuralgia, bleeding of the lungs, Cholera morbus, Croup, Dipthteria...and kindred illnesses. Heals burns, bruises, etc. Best Staple Medicine in the World. Beware of Imitations. Good for Man or Beast.

By the 1880s, health authorities had a basic understanding of contagious diseases and introduced measures such as quarantine under the Public Health Act. Violations of an imposed quarantine could result in fines of $100 (around $3000 today) and/or three months in prison. Such measures, however, were difficult to enforce in small communities.

On March 28, 1896, the Sun carried news from the Police Courts in Twillingate, Magistrate Berteau presiding: On Monday last, Mr. George Rice of Little Harbour, charged with violation of the Public Health Act, by allowing his family to go abroad while his house was under quarantine for Diphtheria: and also for removing the flag before the house was disinfected. He pleaded ignorance of the law and was let off by paying $3.50, being the costs...

Also, Mr. John Spencer, of the same place on a similar charge, having gone to church and other places from a house infected with Diphtheria. He had to pay costs, $2.99.

In defiance of the odds, the four boys of Martha and James survived.

James remarried on November 12, 1892. Five more children were born to him and Annie Eliza, his second wife, over the next twelve years.

Their descendants have spread throughout Newfoundland, Canada and into the US.

Sources:

MUN Digital Archives. The Twillingate Sun. June 24, 1880, to January 31, 1953.

M. A. Bromley, Gleanings From the Sun. Genealogical Abstracts from the Twillingate Sun, 1988.

Cemetery Transcriptions, Long Island, Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland.

Family History Library; Salt Lake City, Utah.